How to perform geoqueries on Firestore (somewhat) efficiently

A geoquery allows you to find points-of-interest that are within a certain range of a specific location. For example, say you have a list of all restaurants and their location: how do you find the ones that are within 5km of the user’s current location?

We’ve gotten the question of how to implement geoqueries on Firestore for many years. In this article I explain why this sort of query was hard on Firestore, how you can now do it much easier, and compare the two approaches.

Firestore before March 2024 — geoqueries using geohashes

Google’s Firestore is a NoSQL database in which values are stored in documents, and each document is stored in a collection. Like most NoSQL databases, Firestore’s main selling point is its scalability — it only supports operations for which it can guarantee the performance at any scale. This becomes especially obvious when you see Firestore’s relatively meager set of query/filter operstions.

In the first 5+ years of its existence, Firestore only supported queries that contains at range and inequality operations on a single field. This is because the field on which you had a range/inequality condition had to be last in the index used for the query, and only one field can be the last. This is due to how Firestore processes queries: it finds the first index entry that meets the query conditions, and then returns all results from the index until it finds the first index entry that no longer meets the conditions — so it returns a single slice of data:

A slice of index results

That made many types of queries impossible, including the geoqueries that we’re looking at in this article. However, it turns out that you could perform geoqueries on Firestore, by using a mechanism based on geohashes.

Geohashes and how to implement geoqueries with them

Geohashes subdivide a 2D coordinate system into 32 smaller regions and assign each of these a character code. You can then split each of the regions into 32 even smaller regions and add another character. In this way a geohash encodes a large region into character strings in such a way that strings with similar prefixes are close to each other.

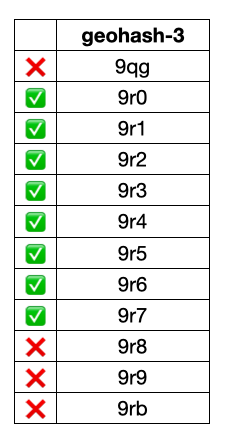

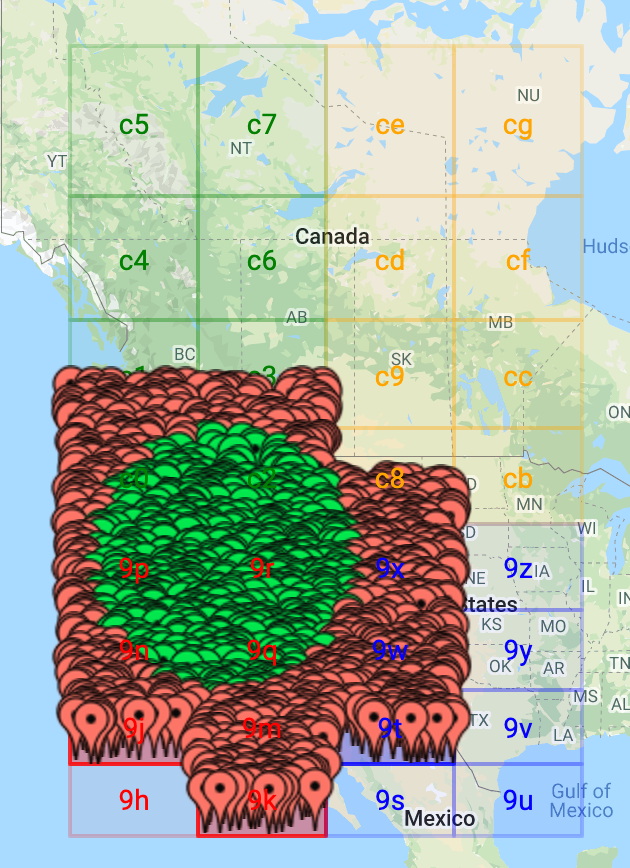

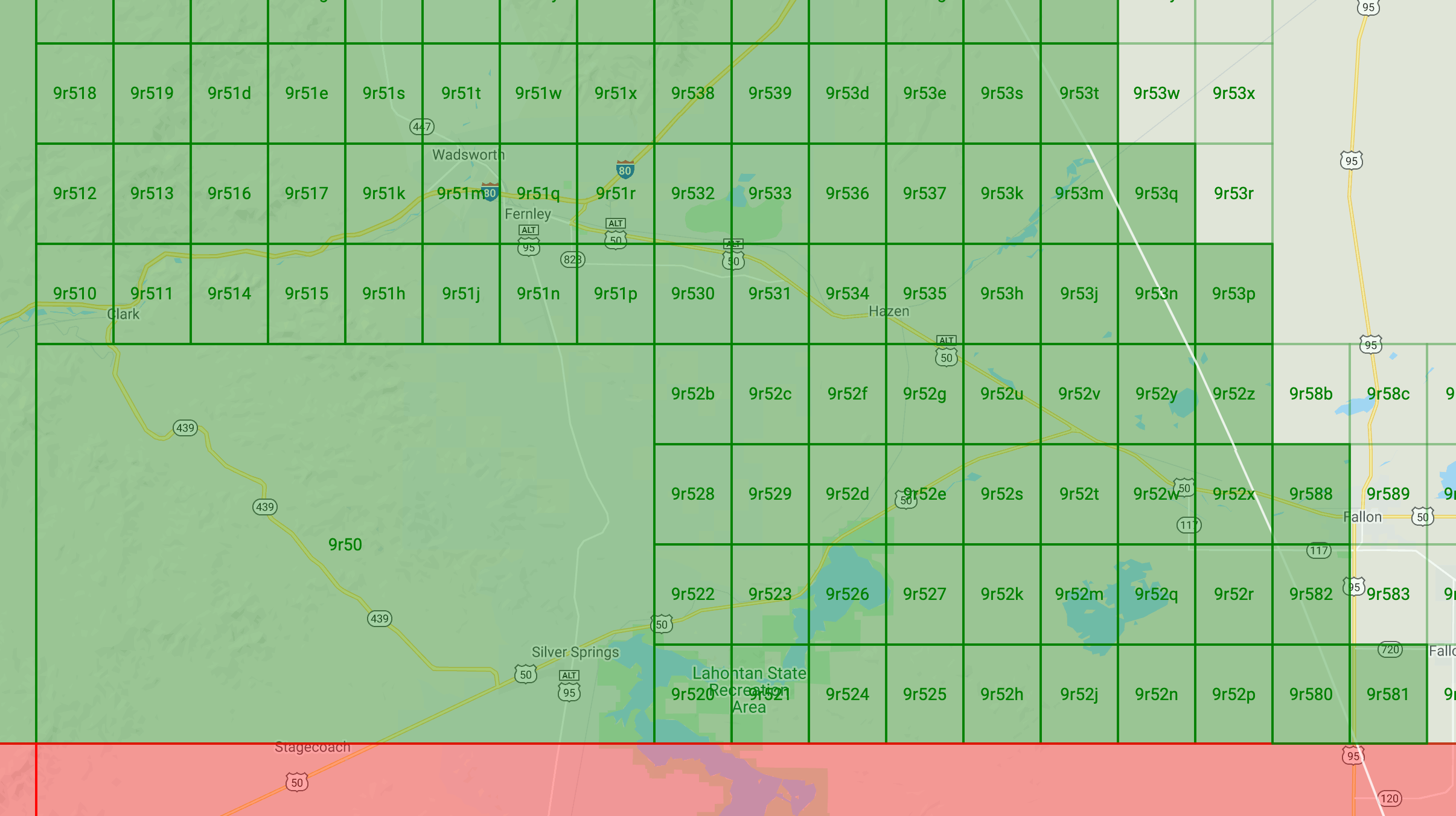

By searching for specific ranges of geohash prefixes you can then find points in that region. For example, this image shows the four geohash ranges that are most relevant when we’re looking for points that are within 250km of Sacramento (the capital of California):

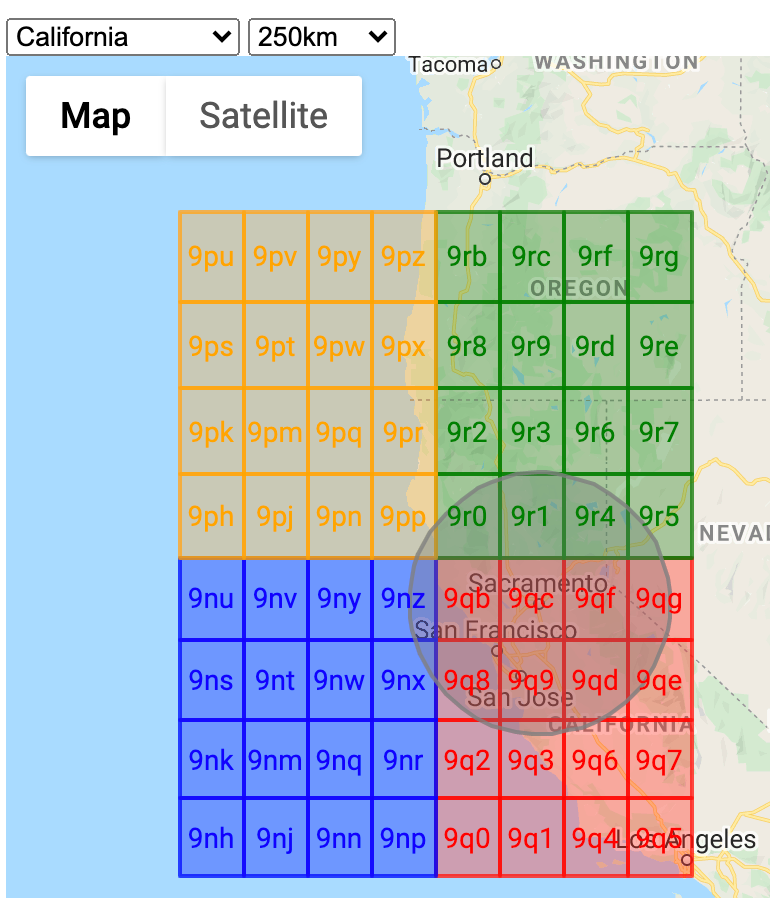

So if we search for all points with the two-character prefixes 9n, 9p, 9q, and 9r, we get all documents in the circle and some documents in the colored rectangles outside of the circle. When we plot those on a map, it looks like this:

The green pins are inside the range we want, the red pins are outside of that area but still within range of the geohashes.

The good news is that we can query the database to find the documents in our range after all. The bad news is that we end up reading many more documents than needed. In the above sample the query reads about 7x more documents than needed. So for every green pin there are six red pins!

In measuring overreads across a large data set, geohash based queries on average read 5.4x more documents than needed (ranging from 3.5x to 14x).

Example of searching for documents within 1,000km of Sacramento:

In this image, the 652 green pins are the points of interest we were actually looking for, while the 3,025 red pins are points that we just have to read because of using geohashes. If we have 1,000 users executing this query once per day for a month:

-

Ideal query: 19,6m documents read = $6.10

-

Geohash query: 110m documents read = $34.20

Reducing the overread factor of geohash based geoqueries

Over time I’ve come up with various approaches to reduce the level of overreading.

By using a prefix length depending on the intersection between the range circle and the geohash bounding box, I was able to reduce the average overreading from 5.4x to 2.8x. Some images from this research:

This approach showed promise, but it was never put into production because work was also being done on improvements to Firestore that would lead to even better improvements.

Firestore since March 2024 — range conditions on multiple fields

Since March 2024, a query in Firestore can have range conditions on multiple fields — sometimes also referred to as multi-field inequalities. This means that we can now actually perform this much simpler query on Firestore to get the documents within a 250km range from Sacramento:

const query = db.collection("geodocs")

.where("longitude", ">=", -124.34075141260412)

.where("longitude", "<=", -118.59710058739587)

.where("latitude", ">=", 36.294675667607216)

.where("latitude", "<=", 40.816534332392784)

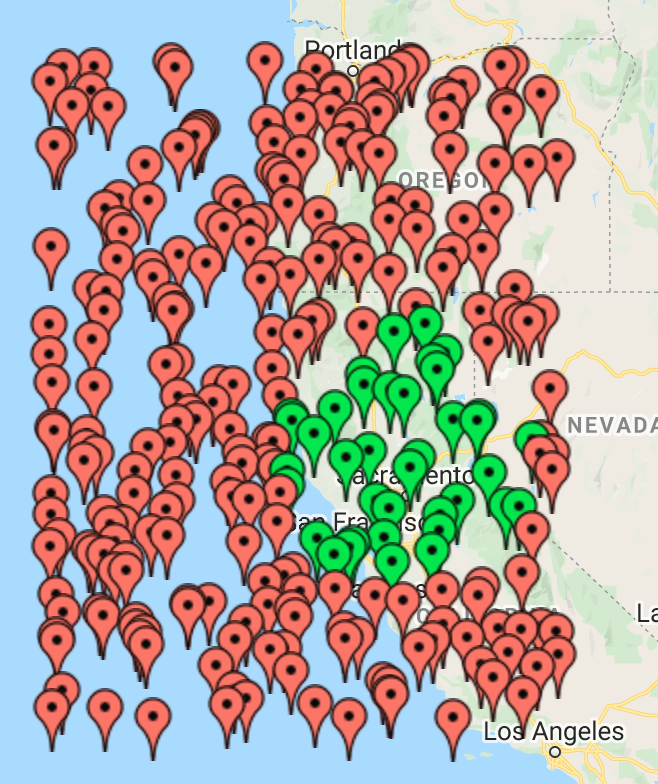

And this gives us a much more reasonable set of results (the data set is different from the one above):

Here our query returned 42 documents, 35 of which are within the requested range — so it reads about 20% more document than needed.

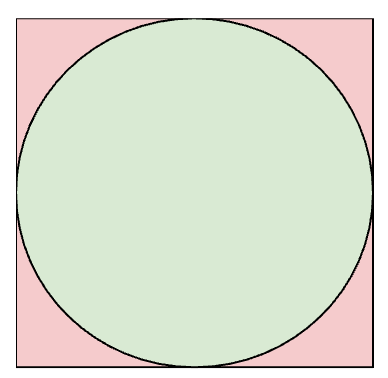

With this new approach the amount of overreading is constant as we’re always looking at this:

Using trig to calculate the difference between the area of the circle and the area of the square in this picture says there’s a 21.5% delta. That is much better than the 5.4x or 2.8x that we had with our geohash based queries.

What’s the catch? You pay for index scans and field order matters

With the introduction of multi-field inequalities the query execution in Firestore has changed, and as a result the performance guarantees and pricing model have also changed.

In the past, queries would always returns a single slice of the data. But in queries with multiple range/inequality conditions, the database may have to scan part of the index skipping entries in there that match some range conditions, but don’t match all of them. So the result can now consist of multiple slices and scanning the index entries between those slices takes effort (which affects performance and cost).

In this query model we pay index scan cost for each of the skipped index entries between the green slices.

In this query model we pay index scan cost for each of the skipped index entries between the green slices.

If we go back to the last screenshot I showed with the 42 documents, using the new query analyzer in Firestore:

PlanSummary {

indexesUsed: [

{

properties: '(latitude ASC, longitude ASC, __name__ ASC)',

query_scope: 'Collection'

}

]

}

ExecutionStats {

resultsReturned: 42,

executionDuration: { seconds: 0, nanoseconds: 43441000 },

readOperations: 45,

debugStats: {

index_entries_scanned: '2512',

billing_details: {

small_ops: '0',

min_query_cost: '0',

index_entries_billable: '2512',

documents_billable: '42'

},

documents_scanned: '42'

}

}

We can see that Firestore scanned 2,512 index entries to find those 42 documents. For the scanned-but-not-returned index entries, Firestore charges 1 document read for each 1,000 entries, so it actually charges 45 document reads for the query.

As the documentation also mentions, the order of the fields in the index may affect how many index entries need to be scanned. So I also ran the query forcing it to filter on longitude first:

const query = db.collection("geodocs")

.orderBy("longitude")

.where("longitude", ">=", -124.34075141260412)

.where("longitude", "<=", -118.59710058739587)

.where("latitude", ">=", 36.294675667607216)

.where("latitude", "<=", 40.816534332392784)

And the analysis results for that are:

PlanSummary {

indexesUsed: [

{

query_scope: 'Collection',

properties: '(longitude ASC, latitude ASC, __name__ ASC)'

}

]

}

ExecutionStats {

resultsReturned: 42,

executionDuration: { seconds: 0, nanoseconds: 77671000 },

readOperations: 44,

debugStats: {

billing_details: {

small_ops: '0',

documents_billable: '42',

index_entries_billable: '1610',

min_query_cost: '0'

},

documents_scanned: '42',

index_entries_scanned: '1610'

}

}

So now Firestore only needed to scan 1,610 index entries (instead of the 2,512 earlier) and that means we’re charged for only 44 document reads (instead of 45 earlier). It’s still more than the 35 documents we actually want to show, but at a stable 1.3x overhead it’s a lot better than the average 5.4x overhead we had with geohash-based queries.

If we have 1,000 users executing this query once per day for a month, it’ll cost us about $7.80. Or compared to the previous situation:

-

Ideal query: 19,6m documents read = $6.10

-

Geohash query: 110m documents read = $34.20

-

Multi-field range query: 25.1m documents read = $7.80

So for this example, geoqueries with the range conditions on multiple fields are over 4x cheaper than geoqueries with geohashes.

Conclusion

Until March 2024 the only way to implement geoqueries on Firestore was through geohash values. While this did work, it leads to reading on average 5.4x more documents than needed.

Since March 2024 you can have range conditions on multiple fields, and can implement geoqueries much more easily and cheaper. This simpler approach reads about 1.3x more documents than needed, so is 4x cheaper than the previous approach.

(exercise for the reader: would having a geohash in the data and using that as the first filter field further reduce the number of index entries that need to be scanned-but-not-returned?)